The Art of Failure

Updated

Tags: programming, research, life

Table of Contents ↓

What happens when the one thing you’ve poured all your energy into over multiple years doesn’t ship? A few years ago, I came to Purdue looking to learn and make an impact. In some ways, I have certainly succeeded: my incredible friends, strong academics, transformative study abroad experience, and steadfast devotion to Purdue Hackers have completely changed the course of my life for the better. However, not everything can always work out perfectly. This post is a story about CodeCheck, my research project for the past three years. Specifically, this is my place to reflect on what CodeCheck was, lessons from my research and development process, and how the lack of concrete results has taught me to find the beauty and meaning in the process of making things.

Conception

CodeCheck was born completely by chance. One day I received an email from Professor Andres Bejarano asking for researchers to tackle an interesting problem: source code plagiarism. I was intrigued and had been thinking about research a lot recently, so I decided to go to the callout. When I got there, I clicked with Andres very quickly, and I became hooked on the idea. Some other interested students and I coalesced into a group, and we got to work. I quickly took a leading role in the group, managing task delegation and nudging towards certain areas of research.

The Problem

It’s no surprise that students tend to cheat off of each other on difficult assignments, especially before the advent of generative AI assistants like ChatGPT. This problem was especially common in computer science classes, where for many assignments the primary objective is to pass a test suite by any means necessary. I’ve heard of particularly creative methods of achieving this, including fuzzing or decompiling the test executable, which may provide some academic value. However, copying a friend’s code isn’t creative and doesn’t teach you anything useful.

Unsurprisingly, Purdue and many other schools try to clamp down as hard as they can on plagiarism, leading to tools like JPLAG and MOSS. While they do a decent job, a whole ecosystem of tips and tricks have been developed to fool them. The big problem comes down to the fact that all tools currently in use by universities reduce down to string comparisons between samples. Additionally, other vulnerabilities exist that make it trivial to get around plagiarism detection, such as MOSS being blind to spacing differences.

To pinpoint the problem: text is easy to deal with; it’s malleable, and humans and LLMs intuitively understand how to manipulate it. When perturbed or obfuscated text is passed to these brittle and short-sighted algorithms, they fail to detect the underlying plagiarism still present in the text. This issue has become especially severe with generative AI available to everyone, ready to rewrite in a way that’s just good enough to fool detectors.

Note: I made the assumption that most large language models (LLMs) would just rename variables and do trivial reordering that didn’t affect the underlying logic of the code, an assertion which was true when LLMs first arrived in the hands of students. This assumption would weaken and eventually become invalid over the course of the following years and many large leaps in LLM capabilities, but I chose to ignore the decreasing relevance of CodeCheck for a very long time to get a chance to dive deep into the problem at hand.

The Solution

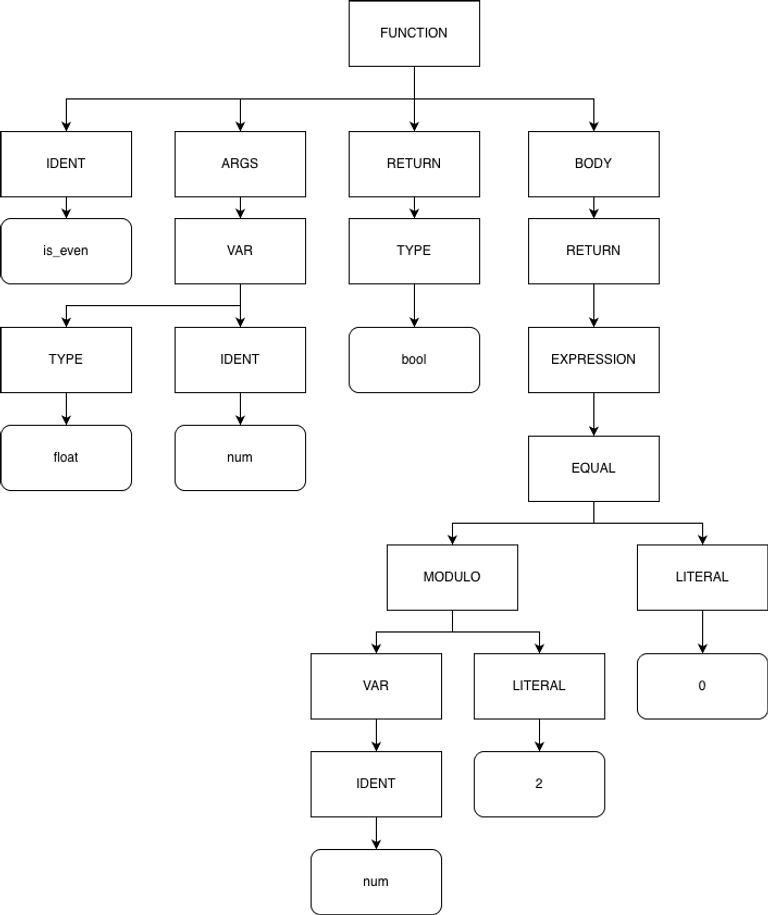

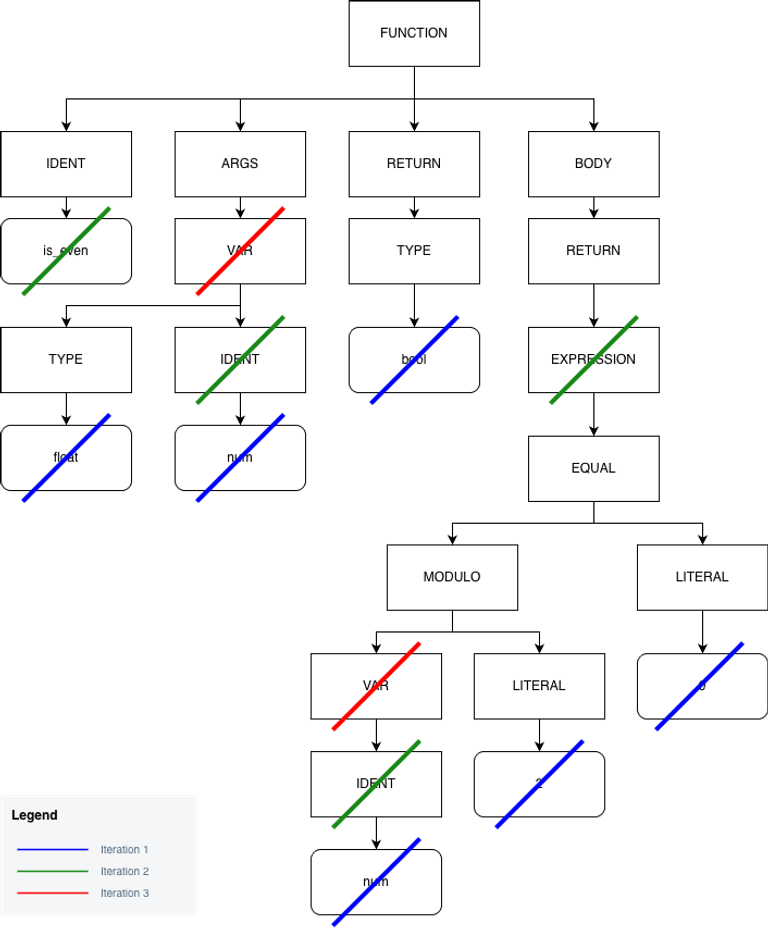

The intuition for my proposed solution is quite simple: what do computers do when they want to get rid of all the junk that comes with plaintext? The answer is to convert it to a data structure that abstracts away all of the characters into a common syntax, organized in a tree-like structure to, in the case of compilers, make instruction generation much easier. You may be able to see where I’m going with this: abstract syntax trees (ASTs). Below is a function and it’s simplified AST representation:

bool is_even(float num) {

return num % 2 == 0;

}ASTs were perfect! They removed all of the nonsense from plaintext, creating a pure representation to operate on. Any variable name could easily be dropped from the tree and comments aren’t considered at all. Further refining the output I was looking for, I would want pairs of line spans , where denotes a range of lines in a source code file . For example, if my model outputs (end exclusive), that means lines 5-8 (inclusive) of file is plagiarized from lines 13-16 (inclusive) of file , or vice versa.

Honeymoon

My group made consistent progress throughout the first year and a half, from fall 2022 to spring 2023. We had regular meetings both amongst ourselves and with Andres. During said meetings we were consistently coming up with new ideas, and at the time, it looked like we would have a prototype ready for presentation very soon. We were all excited when we came across tree kernels, a way of calculating similarity between two trees. I was reading through the paper, and I thought it would be pretty easy to make a good implementation of the concept, but I managed to miss the implications of this important equation:

Here, is a vector of all possible subtrees of tree , and is a recursive, polynomial-time comparison function1. This equation defines the search protocol for the tree kernel and would end up sinking this entire branch of research. To explain why, let’s take a closer look at this equation. The most relevant portion is the recursive condition of , defined as:

Here, is a decay factor, gives the number of children of node , and is the set of child nodes of . This product of sums combined with a product over a recursive set took forever with a naive implementation even on medium-sized collections () of small length programs (). At this point, I had two options: try to optimize it enough that it would work, or give up on it and search elsewhere.

With this computational explosion, I realized we needed to pivot to an alternative method for finding plagiarism. After much debate we settled on a deep neural network as the most promising direction of study and started researching potential model architectures. However, as time passed, many of the members of the group ended up dropping off due to other commitments or increasing class loads, eventually leaving only myself to continue.

The Lonely Path Forward

Fast-forward a year and a half, and I was still trying my hardest to push CodeCheck forward while balancing my own commitments, including an increasingly intense class load, internships during the summer, social obligations, and membership in clubs including Purdue Hackers; it wasn’t easy to do, and I was going a lot slower than I’d like to, but I was still doing research. Andres was incredibly supportive of me during this time, and I’ll always be thankful for his encouragement when I was hitting dead end after dead end.

After learning more about the architecture of LLMs, I decided to try using a transformer to solve the problem. Around this time Andres told me I could consult with an AI professor on campus, something I took advantage of immediately, and good thing I did! After I presented my initial design and implementation, he promptly tore it to shreds and showed me why it wouldn’t work: transformers have no idea of “numbers” or “spans”, so even if the model could hypothetically tell if two files contain content plagiarized from one another, it would have no reliable way to report the line spans back to the overseer consistently. For a real-world analogy, this is why LLMs have so much trouble counting the letters in words or doing numeric math problems: numbers are not something they can “understand”2.

Coming out of this meeting, I was slightly dejected but also relieved that I could cut off a dead end. I had to do some soul searching in order to find my next architecture, but eventually I had a realization: why abandon the AST structure for the text contained within it, needlessly discarding essential position information encoded into the structure? This epiphany led me down a rabbit hole where I discovered graph neural networks and graph attention networks.

Graph Attention Networks: The Best Thing Since Sliced Bread

Graph attention networks, or GATs, are really cool and were honestly the perfect solution to my architecture. Consider the transformer: it operates on each part of a sequence, like a word in a sentence, and informs every other token (read: word) on how it should “shift” its meaning to fit the overall sequence (read: sentence). The real implementation is full of complexities, but a simplified explanation suffices for this post.

Graph attention networks do a similar operation, changing the embedding of the node (and optionally edges, but not in my case) to more closely match the overall meaning from the rest of the graph.

There are many different variations of GATs that use different rules for when and how to update each node with each other node, but the general underlying principle of having other nodes tell a target node how it should update its embedding is the core of it. This was perfect for CodeCheck: I could retain the structural information of the tree (specifically the line numbers of each token) as metadata while allowing the model to operate on the embeddings of each node, not even knowing of the existence of line numbers.

I felt great at this point, but I still needed to define a model around this base component, a task that proved much more difficult than I imagined. The biggest problem was designing a loss function. Finding plagiarism is a multi-layered task constrained by factors including but not limited to:

- Defining “plagiarism” in the context of each assignment, course, department, etc.

- Ensuring the model is adaptable to different those different definitions of “plagiarism”.

- Efficiently considering hundreds of thousands if not millions of combinations of potentially plagiarized files.

- Correctly identifying the exact line spans (of which there can be multiple!) to tag as plagiarism with a razor-thin margin of error.

I originally started with a regressive model utilizing distance intersection over union (DIoU), a function commonly used for object classification. I tried to find new and innovative ways to shove all of the objectives I wanted to track into a single function that would weight all the rewards together, but the model never seemed to be able to handle it. This function needed to be able to either immediately reduce the size of the AST to its relevant parts or do so in iterative steps, both of which I failed to accomplish with a regressive model. After much trial and mostly error I decided to pivot to reinforcement learning.

Reinforcement Learning

For those who don’t know, reinforcement learning (RL) is a subfield of machine learning where a policy, a decision-making model, takes input from the environment and turns it into an action that is then imparted upon the environment. This action can also be graded by a reward signal, an additional data point used to improve the policy, where higher rewards are promoted. I ended up with an advantage actor critic (A2C), where an actor model executes a policy on the data and the critic model grades its performance with a metric called advantage, which refers to how much better an action’s outcome is than the average outcome. A negative advantage means the action taken was worse than average, a positive advantage means the action taken was better.

RL as a field is generally used for longer-horizon tasks, meaning tasks that require thinking about long-term implications of actions the model takes “now” versus “later”, with examples ranging from robotics to LLMs. Intelligently pruning the AST requires thinking about which sequence of small, concrete steps will lead to the most information-dense output, something I believed RL could help with. Specifically, as the tree is pruned, the problem space gets smaller and different nodes need to be removed. In hindsight something like diffusion or flow models may have also worked, but I was interested in RL. My curiosity stemmed not just from its potential application to CodeCheck but also its uses in robotics and other fields, and I wanted an excuse to learn it.

I trained the actor to cut away certain parts of the tree, and the value function to assign rewards based on multiple metrics including code size, relevance, and interpretability.

I spent months shaping the reward and tuning other hyperparameters in hopes of getting my model to perform, but I consistently ran into extreme underfitting. Of the two fixes I tried, one was pretty smart, if you ask me, but the other… not so much.

Band-Aid 1: A Custom Embedding Model

I realized that trying to shove ASTs straight into the main model may lead to issues with data sparsity, since originally I was just feeding the vectors straight in as one-hot encodings (where a node is represented by a single 1 in a certain position and 0s everywhere else). To remedy this I created a small embedding model with what I think was a pretty smart objective: do triplet loss on the embedding of the text description of each node in the language’s grammar. For example, if I had a node from C with label IfStatementCondition, I would try to bring it closer to a similar node from C++ with label IfStatement and farther from a node with label VariableDeclaration. The idea was to give the embedding model an understanding of how nodes with different names in different languages were actually similar semantics-wise and should be placed together in the latent space. I also had auxiliary objectives targeting the language of the AST the node came from and a preorder traversal of the node’s AST to try to get the embedder to understand the tree structure and what made languages different.

I was quite proud of this embedding model, and it certainly did something, but unfortunately it didn’t yield the performance improvements in the main model I had hoped for. It’s possible I just needed to tune more hyperparameters, but I was a one-man show and starting to run thin on patience.

Band-Aid 2: Synthetic Data

Unsurprisingly, people tend to not be very forthcoming about copying off of others in an academic setting, and said cheaters are not likely to donate their code and the code of their accomplice to open datasets I can use to train off of. After a long string of disappointing datasets, I decided to try a strategy I had avoided for the longest time: synthetic data.

After all of the discourse on model collapse, I had wanted to avoid using synthetic data at all costs. I even went so far as to design my own labelling suite to try to make it easier on myself and my team to label our own data, but due to the unavailability of any coding assignments at all, that initiative failed. I decided to just hope for the best and see what happens, since I didn’t really have any other options. The good news is I didn’t have any issues with the quality of data generated by the LLMs. The bad news is even with their extensive capabilities, LLMs were unable to produce data at large enough quantities for me to use in CodeCheck.

LLMs failed on many measures, but their two biggest drawbacks were inconsistency and cost. LLMs are great when you want them to write an email for you, but terrible when you want consistently-formatted outputs3 for a problem that fundamentally requires some creativity and cross-problem application. After many iterations of prompt tuning I was only able to get an around 70% success rate at generating samples. Even achieving that relatively low success rate was a very interesting challenge that I will touch on now.

Aside: Bending LLMs to Your Will

I like to think of LLMs as occasionally malicious toddlers that generally want to do exactly what they want, not what you want. After learning my lesson trying to shove line numbers directly into my own transformer in the first version of CodeCheck, I realized I needed to keep numbers as far removed from the LLM as possible. To do this, I instead leaned on a markup language many LLMs know as second nature: XML. I would instruct the LLM to generate XML tag pairs <plag IDENTIFIER>CODE</plag> to wrap the code the LLM decided was plagiarism. To demonstrate, below is an example of two generated snippets of “plagiarized” code:

def sort_numbers(arr: list[int]):

for i in range(1, len(arr)):

key = arr[i]

j = i - 1

<plag while>

while j >= 0 and key < arr[j]:

arr[j + 1] = arr[j]

j -= 1

arr[j + 1] = key

</plag>void sort(int arr[]) {

int n = arr.length;

for (int i = 1; i < n; ++i) {

int key = arr[i];

int j = i - 1;

<plag while>

while (j >= 0 && arr[j] > key) {

arr[j + 1] = arr[j];

j = j - 1;

}

arr[j + 1] = key;

</plag>

}

}This method, designed to look and act somewhat like tool calls, was tailored to allow LLMs to say where the plagiarism was without needing to give potentially faulty line numbers. When the LLM managed to generate matching tag pairs4, I had parsing code that would go through and remove the tags and replace them with the actual line numbers. This system, along with other failsafes like a very detailed prompt and error checking on opening and closing tags, allowed me to achieve much more reliable data generation.

However, even with all of these measures, cost crept in as the silent killer. I am fortunate to have a Mac that can run some of the latest LLMs completely on-device, but at the scale I needed the tokens per second was far too low; I would need gigabytes if not terabytes of data, and I didn’t have infinite time. This problem led me to rent GPUs from RunPod, which of course has actual costs associated with it instead of me being able to leech off of Purdue’s power with my Mac. RunPod had much better token per second performance, at the cost of draining my bank account very, very fast. I also looked into alternative hosts and APIs for doing what I needed, but to no avail. In the end I realized that even with the speed I was going at and using faster LLMs, this just wasn’t going to work.

The Long Tail

Many different events in my life led to me deciding to close the book on CodeCheck. In August, I took a trip to San Francisco to visit friends and by chance ran into the co-founder of Era Labs, Liz, with whom I brought up a project I had envisioned called Beacons. We hit it off, with me eventually joining Era Labs as a fellow. This newfound position gave me a project I was really excited to work on and greatly reduced my already dwindling interest in working on CodeCheck. I’ve realized that I do much better with projects when I have small, consistent ships reinforcing my belief that I’m making something awesome; CodeCheck lacked these entirely. I felt like Sisyphus pushing his boulder, constantly being thrown back down to the valley by yet another stupid problem.

Around this time, graduate school became a real thing I needed to think about. I realized I had a choice: either continue trying to grind CodeCheck and hope I could miraculously get eye-catching breakthrough results, or focus on researching fields of interest and professors who would bring me to the next level of understanding in what I care about. I strongly dislike giving up on projects, especially ones I’ve spent so much time on, but with all that was happening and the pressure to go through another application cycle, the scales tilted in favor of stopping work on CodeCheck.

Of course there’s also the elephant in the room: much-improved LLMs. By the time I had gotten to this point in September 2025, LLMs had become scarily good at writing code and very few of them had any problems helping with plagiarism. There’s a difference between trying to match between students within a few sections and potentially a few previous students’ assignments versus the entirety of human knowledge! I did have some ideas to fix this problem such as incorporating some LLM-generated outputs given the assignment details as “students”, but after dealing with such a data desert I had no willpower to continue to try to fight LLMs.

All of these things had various levels of impact on my decision, but the biggest problem that wouldn’t get out of my head was the overwhelming complexity of the problem and absence of good data. If either of those problems didn’t exist, I may have been able to push forward, but unfortunately plagiarism is an inherently subjective topic, and I’m currently bound by the laws of the universe to have limited time to spend on generating potentially useless synthetic data. That’s not to say I believe this problem is impossible to solve with current methods. I firmly believe that if someone devoted their master’s thesis or PhD dissertation to the problem it would likely be possible to create a system like the one I envisioned. My friend John has, throughout the years, proposed many interesting areas of research I didn’t have time to explore such as alternate transformer models, RL methods, fine-tuning other models, and data aggregation architectures that may be the key to finally unblock me. Alas, other more interesting problems have now fully captivated me, so after writing this post I will be satisfied with the work I’ve done.

The story of CodeCheck may be over, but I will never forget the ways it changed me and helped to mold me into who I am now.

Venturing to the Ends of the Earth

I would consider myself to be a pretty rabbit hole-prone person; if I find an interesting thread, I will more than likely pull it until I find myself buried under a mountain of twine. CodeCheck hijacked this instinct and put it into overdrive. I found myself going through so many papers I couldn’t even keep up with my own mind at some points. This obsession didn’t even cover the many, many hours I spent scouring the internet for plagiarism datasets, only to find none. Even then, I became the world’s best detective for plagiarized code, and I’m happy I did.

Rarely do I become so dedicated to a single project, but CodeCheck showed what could happen when I let it become my sole star. Seeing myself go to all these lengths makes me very excited for whatever rabbit hole next catches my eye. If there’s a very important lesson I learned, it’s choosing what objectives and subjects to peruse and which to leave until later. Structured information is the best possible fuel for me to make insights and along with my reluctance to give up, it’s a potent combination.

CodeCheck, the Catalyst

CodeCheck has, for better and worse, affected me in so many different ways. Before I started CodeCheck I knew I wanted to go into machine learning, but I had pretty much no idea how any part of the math worked or which subfield I wanted to explore. As CodeCheck progressed I was forced to confront these questions. I slowly became very partial to RL and specifically hierarchical reinforcement learning, where multiple policies work together in a delegation fashion to achieve complex tasks by distributing the knowledge for doing so across different levels of complexity. I was also able to get into a bit of graph theory and graph neural networks, two topics I was vaguely aware of starting CodeCheck but now I find to be very interesting topics.

The impact CodeCheck has had isn’t limited to my academic pursuits. One day Matthew, the previous president of Purdue Hackers, invited me to a CS partners lunch where clubs would go and chat with companies regarding sponsorships. By chance I happened to sit across from a PhD in computer science who works at Peraton Labs. We hit it off talking about our research experiences, one thing led to another, and I got an internship at Peraton Labs over the summer! When I first started at Labs I was placed on the networking team; said team had some amazing people working on it but I knew deep down I wasn’t super interested in the subject matter. However, one day I overheard some of my co-interns discussing a graph neural network problem. I asked them to have a meeting with their supervisor, and after using my knowledge of graph neural networks gained through CodeCheck I got on the team! I then spent the rest of the summer working on something very exciting, and I wouldn’t have gotten the opportunity to do so without CodeCheck.

There were of course days where I felt down, even hopeless, at the thought of trying to continue the project, but when I would eventually push through and continue working my resolve was strengthened beyond my wildest dreams. I learn by failure, and the setbacks I encountered while designing CodeCheck’s architecture taught me more about how to design machine learning architectures than any class I took during my undergrad. I will take the skills and knowledge I gained forward with me to wherever I go next, ready to climb my next hill with all the strength I’ve got.

Build, Fail, then Build Again

I am endlessly thankful to Andres and everyone else who supported me while working on CodeCheck and excited to work on whatever’s next. CodeCheck may have been a failure in some respects, but in others it was a work of art. The intricacies of building a complex model to find plagiarism created something nonfunctional in this specific case but is still beautiful nonetheless. Every step was dutifully thought out by myself and others, and the journey mattered much more than the destination. I’m reminded of a quote by Larry Page: “It’s very hard to fail completely if you aim high enough”, and I don’t think there’s a word to describe how high I aimed; shooting for the moon would be an understatement.

CodeCheck was yet another entry in my endless cycle of building. I ideate, I create, then I either ship or learn what to do better next time. I tend to oscillate interest between software and hardware projects, so I’ve really enjoyed working on Beacons since they give me that physical presence CodeCheck never would’ve had even if it had worked out perfectly. I don’t know where I’ll be or what I’ll build next, but I’m excited for whatever the world sends my way. Anything and everything can contribute to the art I make.

Footnotes

-

Song, H.-J., Park, S.-B., and Park, S. Y. Computation of program source code similarity by composition of parse tree and call graph. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2015:429807, 2015. doi:10.1155/2015/429807. ↩

-

Recent research has shown LLMs use really cool latent space structures to compute operations such as addition. While this is a very interesting finding, I do not believe this constitutes a fundamental understanding of numeric operations, especially since LLMs still tend to fail on more complex mathematical problems. ↩

-

Yes, I know about Structured Output Mode, but generating valid source code interspersed with arbitrary XML tags isn’t exactly a supported use case. ↩

-

An event that was, for some reason, rarer than you’d think given the terabytes of XML and HTML these models have ingested. ↩